Twitter and the Spread of Academic Knowledge

Serendipity without physical proximity? Maybe, maybe not.

This article will be updated as the state of the academic literature evolves; you can read the latest version here. You can listen to this post above, or via most podcast apps here.

Before we get to this week’s post…

Announcement: There is still time to apply to work with me on Innovation Policy at Open Philanthropy! Details here.

Meta-announcement: if you have an announcement that you would like to disseminate to readers of New Things Under the Sun (17,000+ followers), please email me the details and if appropriate I will include it as an announcement ahead of the next newsletter (free of charge). If I get a lot of announcements, I’ll bundle them into a dedicated announcements post, like the one I put out earlier this month.

Announcements that would be a good fit for this are grant opportunities, conferences, and job opportunities. But I’m open to other ideas too. Just make sure it’s relevant to readers of New Things Under the Sun.

On to the post!

A classic topic in the study of innovation is the link between physical proximity and the exchange of ideas. I’ve covered this pretty extensively on New Things Under the Sun, and one theme has been that scientists/inventors have various ways of keeping up with relevant new discoveries: they read journals, attend conferences, talk with people in their professional circle, etc. Especially with the advent of digital communication technology, none of that is particularly constrained by geography anymore - you don’t need to be close to where a discovery happens, in order to learn about it. While these methods are pretty good for keeping you up-to-date on things happening in your particular niche, they aren’t great for serendipity. If you don’t know that a field from outside your niche is relevant to your work, how do you know to read the journals, attend the conferences, or talk to people in that field?

One thing that does provide serendipitous encounters with new ideas is physical proximity: being around people who work on lots of different things means you can bump into people and learn what they’re working on, even if you wouldn’t normally expect their work to be relevant - but sometimes it is.1 But I’ve long been interested in a relatively new kind of serendipity engine, which isn’t constrained by physical proximity: twitter (later renamed x, but forever twitter to me). Lots of academics use twitter to talk about new discoveries and research. Today I want to look at whether twitter serves as a novel kind of knowledge diffusion platform.

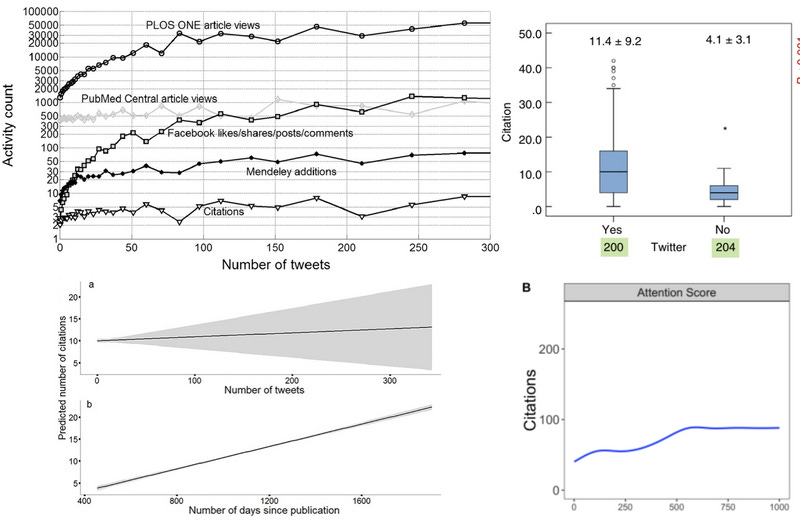

We’ll mostly look at citations, an imperfect but widely available way of assessing the impact of a scientific paper.2 We could also look at article page views or downloads, but citations arguably provide a stronger signal both that an academic author learned about an idea and thought it was related to their work. Many papers have started by gathering data on how often academic papers get tweeted about and compared that to the number of citations they receive. These are just observational papers, documenting correlations in the wild, but they generally find that papers that get more tweets also get more citations, as indicated in the set of figures from four different papers below.

Let’s quickly walk through this figure. In the upper left, we have a figure from de Winter (2015), which looks at articles published in PLOS ONE in 2012 and 2013. The figure compares the number of tweets (horizontal axis) to various average outcomes. The bottom line in this figure shows citations, which move (slightly) up and to the right. Meanwhile, the upper right figure from Jeong et al. (2019) compares the number of citations for roughly 400 articles published in coloproctology journals. Those that got a tweet tended to have more citations. On the bottom left, we’ve got a figure from Peoples et al. (2016) which looked at tweets and citations in ecology papers. The figure shows how their statistical model predicts citations as a function of tweets (also as a function of time); again, (very) slightly up and to the right. Lastly, in the bottom right, we’ve got a figure from Lamb, Gilbert, and Ford (2018) looking at ecology and conservation papers. The figure shows the predicted number of citations as the number of tweets increases, for a paper that is average along other dimensions. A number of other papers document similar relationships, for example in fields like urology, ornithology, orthopedics, AI research, political science, and communication.

If twitter is acting as a way to spread ideas, we would expect to see this kind of correlation. But other stories would also give us the same correlation. Papers that people think are good are more likely to be tweeted about, but also more likely to be talked about offline, more likely to publish in good journals, and more likely to be cited. The fact that there is a correlation between tweeting and citation doesn’t tell us whether twitter is mediating awareness of the paper or if it’s merely that good papers get cited and also talked about on twitter. To estimate whether twitter is having an impact on knowledge diffusion, we need to look at scenarios where tweeting about a paper is unrelated to the paper’s quality.

Chan et al. (2023) argues they have found one such scenario in economics. There is a popular online publication series, called VoxEU, where economists write accessible short columns, often about their own research. These columns often get tweeted about, which also drive twitter attention towards the underlying academic research. While much of this tweeting is driven by how interesting people find the research, Chan and coauthors also find it’s related to when the VoxEU columns are published. Specifically, columns that are published on weekdays and in the summer are more likely to be tweeted about. They argue the timing of when columns are published is not related to how interesting the underlying research is, and so this provides a natural experiment to assess the impact of tweeting on citations. The basic idea is, if you know the typical relationship between tweets and subsequent citations, and you also know the typical relationship between publication date and number of tweets, then you can back out the impact of a tweet that you received purely due to differences in the timing of publication.undefined That’s arguably the impact we’re interested in: tweets that are unrelated to a paper’s underlying quality.

When they do this exercise on a sample of about 1,000 articles published on Friday through Monday, they find receiving any tweets about your research is associated with about 16% more citations. Note though that the error bars on this are pretty wide - a 95% confidence interval would include “no effect” (though a slightly tighter confidence interval of 90% would not). That’s a theme we’ll be seeing a lot in this literature.

There is also a growing literature that directly attempts to measure the impact of tweeting (unrelated to paper quality) through a different method: twitter experiments.

RCT Evidence (Randomized Control Tweeting)

There have been several studies that randomly select some papers to tweet about, some papers not to tweet about, and then compare the citations received by papers that were tweeted about to those that were not. Since papers get randomly allocated to the tweeting or “no tweet” side of the experiment, any systematic difference in citation rates can be attributed to the impact of tweeting. When we look at these randomized control tweet experiments, rather than observational data, we don’t see much evidence that tweeting affects paper citations.

Tonia et al. (2020) report on an experiment on 130 original articles published in the International Journal of Public Health between December 2012 and December 2014. Half these articles received a brief social media promotion on Twitter, Facebook and a blog post, and the other half did not. They then followed up about 2-4 years later (depending on when the paper was published), but found the promoted papers did not receive a statistically significant number of additional citations.

One shortcoming of Tonia et al. (2020) is that the social media intervention came from the journal’s twitter account, which wasn’t highly followed (403 followers at the time the study started). Maybe that’s just not enough people to test the knowledge diffusion hypothesis.

But another study, Branch et al. (2024), doesn’t have this issue and gets similar results. Branch et al. (2024) is a collaboration between 11 active researchers who are also influential twitter users, most with more than 5,000 followers - for comparison, this would put them in the top 13% by follower count, in a sample of academic economists on twitter. Each of the authors picked a journal in their field (for example, Journal of Animal Ecology, Polar Biology, Ecological Entomology, etc.) and then each month five research articles were randomly selected. From this set of five, one was randomly selected to be tweeted about by the participating twitter account, and the other four were not tweeted about. Branch and coauthors tweeted brief summaries of the paper in their usual style of tweeting about papers. Three years after each tweet, the authors collected data on the papers that had been tweeted and the other four from the same journal that had been randomly selected not to receive a tweet. Across the 110 papers that were tweeted about and the 440 that were not, the ones tweeted about did not receive a statistically significant number of additional citations.

So that’s two studies that find tweeting does not influence citations over a multi-year period. On the other hand, there are two more studies that do. But both of these studies have come under scrutiny since publication. Luc et al. (2020) looks at an experiment to tweet or not tweet 112 representative articles published in Thoracic and Cardiovascular surgery journals in 2017-2018. A year later, they found tweeted articles got 3.1 citations, compared to 0.7 among the non-tweeted group, which was statistically significant. However, a later attempt to reconstruct this dataset and replicate this result, by Phil Davis over at the Scholarly Kitchen website, was not able to find a difference between the two groups. In another case, Ladeiras-Lopes et al. (2022) report on an experiment to randomly promote 347 articles published between 2018 and 2019 in European Society of Cardiology journals, and randomly not promote another 347. Roughly 2.7 years later, they found the tweeted articles had received a statistically significant 12% more citations than the non-tweeted articles (though Ladeiras-Lopes and coauthors point out that tweeted articles also benefited from 24-hour open access). A reanalysis of their data, again by Phil Davis, successfully replicated this result, but found the statistical significance of the result was sensitive to choices in the method of statistical analysis. Arguably preferable methods found the difference between the two was not statistically significant.

Interlude

So it seems that twitter isn’t the vehicle for serendipitously discovering unexpected papers, that I personally hoped it would be.

Well, not so fast. There are two wrinkles that warrant further study I think.

First, it is notable that every study listed here actually does find tweeted papers receive more citations than ones that are not tweeted. It’s just that the differences are not statistically significant, or not replicable, or not robust. For example, Branch et al. (2024) find that papers they tweeted about are 7-12% more highly cited than papers they did not tweet about. Ladeirras-Lopes et al. (2022) and Tonia et al. (2020) also find similar effect sizes. These levels seem plausible to me - as a point of comparison, Azoulay, Wahlen, and Zuckerman Sivan (2019) find that elite life scientists who unexpectedly pass away and are subsequently memorialized in journal articles see a similarly sized bump to citations to their work.

The trouble is citations are so noisy that given the sample sizes in these twitter studies there is a reasonable chance the tweeted papers would have gotten this many additional citations simply by chance, and so we cannot be confident the increase in citations (in the neighborhood of +10%) is statistically significant. For example, Branch et al. (2024) estimate they would need a study that is 3-7 times larger than theirs to reliably detect effect sizes of this magnitude. That suggests to me that either a larger study, or perhaps a meta-analysis pooling results across all these studies might find that, indeed, tweeting can increase citations on the order of 10%.

A second wrinkle: I don’t think we should assume the impacts of tweeting will be uniform across articles. Recall, researchers already have a lot of ways to learn about relevant work - they read the journals, attend the conferences, talk to their network, etc. I would anticipate that the impact of twitter would be much attenuated for papers that are likely to diffuse through these traditional channels; whether anyone tweets about them or not, you’ll learn about these papers. But for papers that might not normally diffuse via these channels, the impact of twitter might be a lot stronger, because if you see a tweet you learn about it, and if not, you don’t. I described some similar dynamics in the post Steering Science with Prizes. In that post, we found some evidence that scientific prizes have a bigger impact on citations to work that is less well known at the time of the prize.

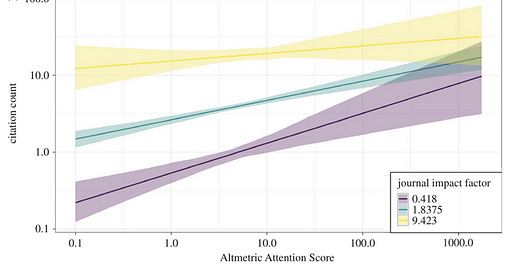

Finch, O’Hanlon, and Dudley (2017) provides some observational evidence consistent with these effects for twitter too. Their study looks at more than 2,500 articles published in 10 ornithology journals between 2012 and 2016 and look at correlations between social media attention and subsequent citations. Unlike any other study (as far as I can identify), they look at this effect separately for journals at different impact tiers. They find the correlation between social media attention (mostly twitter) and citations is substantially stronger for articles published in journals with low impact factors, compared to high ones. In other words, for articles in journals that don’t normally attract a lot of citations, getting mentioned on twitter a lot is associated with more citations to a much stronger degree than is the case for articles published in highly cited journals.

Related, if twitter is most useful for serendipity, it might be that it has the largest impact on citations from outside the field. These citations might be more valuable than average (since connecting ideas from across disciplines is associated with high impact), but they’re probably not common and you would need a large study to detect them.

What’s a Citation Really?

OK, so while we have probably ruled out that twitter has a very large impact on citations, I’m not sure we’ve ruled out the possibility that it has a small average effect, and possibly a larger effect for articles that would otherwise be less well known.

But a critique of this entire exercise is that it’s focused on citations. I’m ultimately interested in whether twitter is a platform for disseminating important knowledge for innovators. While I think citations are a useful measure of knowledge flows at sufficiently large scales, it’s also true that the majority of citations made don’t seem to be particularly important.3 I think it’s plausible that citations formed via twitter might be disproportionately of the unimportant type. Maybe the really important stuff you learn through the usual channels, and twitter just helps you round out your citation list before submission to a journal (and not even very much).

For that reason, Qiu et al. (2024) is quite helpful. Their study is also a randomized control trial, where some papers get tweeted about more, and others do not. Unlike the other papers discussed so far, Qiu et al. (2024) is not focused on citations (though they do say they plan to look at that in the future), but instead on hiring decisions. They set up their experiment around the 2023 economics job market for new PhDs. In economics, it is the norm for students to prepare a “job market paper” which showcases their research to prospective employers. In this experiment, tweets about their job market papers were submitted by 519 new PhDs. All of these tweets were tweeted by a specially created twitter account designed to promote job market candidates. Qiu and coauthors then arranged for 81 academic economists with more than 4,000 twitter followers to tweet about a random subset of these submitted tweets.

They then look at how the number of job interviews, the number of invitations to fly out and present their research to the potential employer, and the number of job offers received by students who receive a tweet about their work from a large twitter account and those that don’t. Echoing the findings of our earlier papers on citation, they find that applicants who (randomly) get a tweet about their work get more interviews, more flyouts, and more job offers, but also that these results are often not statistically significant. They can never reject zero impact of tweeting on tenure-track jobs outcomes, though depending on what factors they adjust for they can sometimes find the effects of tweeting is statistically distinguishable from zero for all job outcomes of PhD economists.

What’s useful about this study is that, unlike the decision to cite, hiring decisions have real stakes. If twitter actually does disseminate valuable knowledge that would not be circulated via conventional channels, one place we could see that is in hiring. It’s quite common for hiring committees to receive hundreds of applications, and so they don’t have the time to read every job market paper they receive. So having heard about the research previously - via conferences, peers networks, or twitter - could be very valuable in allowing a paper to get past the first cut and examined more closely. If people subsequently go on to hire those people, that suggests twitter is playing an important role in disseminating information people find valuable, that they wouldn’t otherwise see. The paper provides some weak evidence this does happen, though not especially for tenure track jobs.4

So in the end, I think this experiment is broadly consistent with the other findings from randomized controlled trials on the effects of twitter. Does twitter matter? Maybe!5

As a final point, the fact that randomizing papers to be tweeted about doesn’t yield unambiguously large effects on academic citations is one more (small) reason to think academic citations contain some useful information; they’re not whipped around wildly based on something as seemingly inconsequential as a tweet.

Thanks for reading! As always, if you want to chat about this post or innovation in generally, let’s grab a virtual coffee. Send me an email at matt@newthingsunderthesun.com and we’ll put something in the calendar.

See the posts Innovation at the office, Local learning, and Why proximity matters: who you know for some discussion.

See the post Do academic citations measure the impact of new ideas? for more discussion.

See Teplitskiy et al. (2022), discussed in the post Do academic citations measure the impact of new ideas?

It’s also possible that the impact of the experiment is less about increasing awareness, but rather the impact of (perceived) endorsements from academic economists on twitter. As some evidence for this, the paper does find the effects of tweets are a bit stronger when the tweeter has more academic citations. Note the two effects can also interact - more academically successful tweeters might be disproportionately likely to be followed by academic hiring committees, and the tweet of an academically successful peer might be more likely to prompt someone to read past the abstract of a paper and become “aware” of its content. But on the whole I am skeptical this is a story about the power of endorsements, rather than awareness. You can see some examples of typical tweets in this experiment here - they don’t look like endorsements to me. More broadly, the authors use an LLM and an RA to score tweets on a range from 1 (no endorsement) to 5 (very strong endorsement) and rate the average tweet around 1.7.

There has been some controversy about whether these kinds of studies are ethical to do. On the whole, I (unsurprisingly) think innovation matters a great deal and the potential to learn about the factors affecting it substantially outweigh potential costs from interfering with our twitter interactions.