This article will be updated as the state of the academic literature evolves; you can read the latest version here. You can listen to this post above, or via most podcast apps here. I was late recording the previous post’s audio version, but it’s now available here.

Announcements

Nature has a nice write up of the UK Department of Metascience, whose latest grant program Open Philanthropy is co-funding. We want to support science agencies and organizations interested in using science to improve their policies and processes. If that’s you, email me!

NeuroLibre Day: On September 27, in Montreal, there will be a symposium on reproducible publishing and the beta-releast of NeuroLibre - an open-source server for hosting reproducible research objects.

Email me to suggest an announcement for the next newsletter. On to the post!

Here’s a chart from FT columnist John Burn-Murdoch, showing how language about progress in English, French, and German books has changed over the last few centuries. The share of words associated with progress rose during the era of industrialization, but is down since the 1950s. Meanwhile, words associated with worry and risk are up.

Who cares? Well, there’s a school of thought that cultural attitudes towards progress are an important driver of innovation. The general idea is that societies which valorize innovation and progress get more of it: they inspire more people to become innovators, their governments place a higher priority on supporting innovation in regulation and education policy, and their affluent class are more willing to invest in the future. Indeed, Burn-Murdoch shows that the prevalence of progress-oriented language rises in England well before Spain, and also that GDP per capita began to rise in England before Spain as well.

Burn-Murdoch’s chart is inspired by Almelhem et al. (2023), which looks at how written language in England changed between 1500 and 1900. Their goal is to find some quantitative support for an influential theory of the industrial revolution from economic historian Joel Mokyr. Mokyr (most notably in his book A Culture of Growth) argued that one important cause of the British industrial revolution was a belief in the possibility of progress and the virtue of finding tangible improvements in things like industry. When this belief collided with the fertile ground of Britain’s artisanal class and a growing base of useful knowledge (derived in part from the sciences), then sustained productivity growth began. Almelhem and coauthors want to look for evidence consistent with this story by seeing if there is an uptick in language about progress in the runup to the industrial revolution.

To do that, they use word frequency data for more than 170,000 works from the Hathitrust digital library, a collaboration of research libraries that has digitized their holdings. Their analysis focuses on all the English-language works published in England over 1500-1900, in this collection. They pull three different kinds of information out of these texts:

Topics discussed: there is a standard set of algorithms in natural language processing which seeks to identify “topics” as sets of words that tend to co-occur in documents. They use these algorithms to construct 60 distinct topics that are discussed in their corpus.

Progress sentiment: how frequently does the work use the words progress, advance, improvement, rise, stride, amelioration, or betterment (all synonyms for progress that do not have double-meanings and were in use prior to 1643).

Industrialization focus: how much does the work use words found in the index of Appleby’s Illustrated Handbook of Machinery, vol. 1-5.

As an additional step, they do some complicated work to measure how closely related each of the 60 topics is to one of three major categories: science, religion, and what they call political economy.1

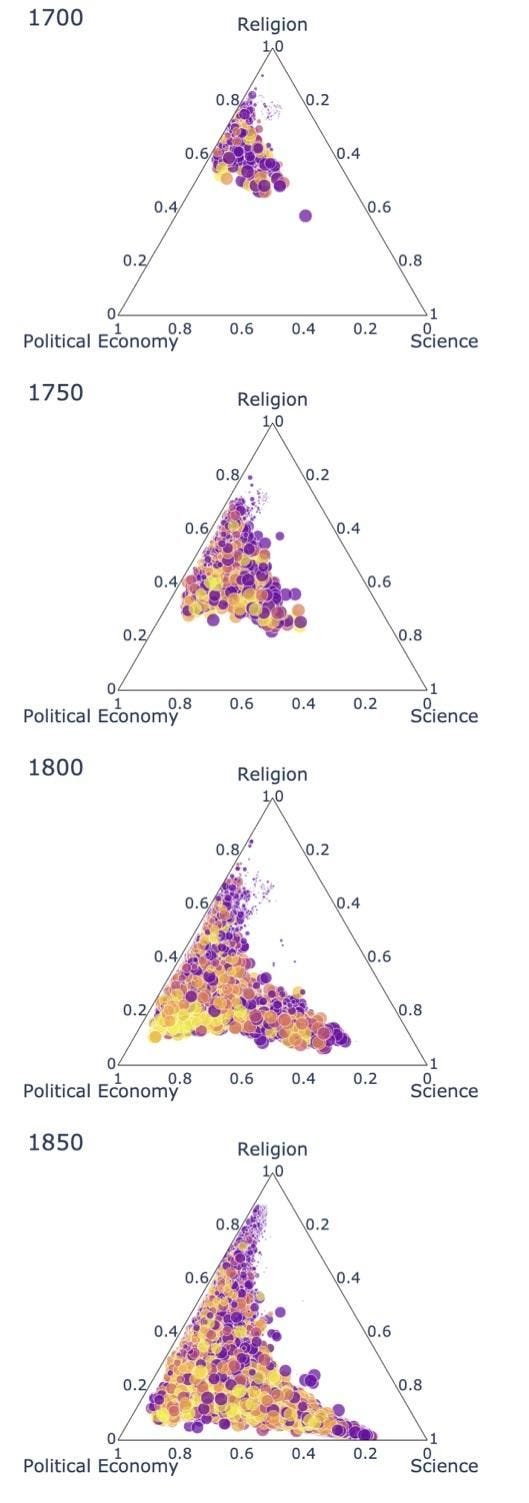

Here’s a chart that is packed with information from this exercise. Let’s walk through what it shows.

First, note that we have four triangles, corresponding to four different 50-year periods: 1700-1750, 1750-1800, 1800-1850, and 1850-1900. Within each triangle, we have a set of circles, each of which corresponds to a text published in that time period. The position of these texts tells us how closely related they are to the three main categories, science, religion, or political economy. We can see that over the time period covered, there was significant growth in the number of texts about science and political economy.

One thing that’s notable is that whereas many texts are about religion and political economy (they appear roughly halfway between the two vertices, on the left edge of a triangle), and many texts are about science and political economy (stretched out along the base of the triangle), we don’t really see any texts that are about both religion and science.

Now let’s turn to the colors in these diagrams. The yellow colors correspond to more progress-oriented language. Overall the figures get much more yellow as time goes on, matching the Burn-Murdoch chart we opened with. But we can also see that the political economy axis, which is associated with words of human institutions (law, govern, trade, etc.) is the center of gravity for progress sentiment. So the growth in progress oriented language was associated with growth in a new kind of literature, which discussed human institutions explicitly.

Finally, the size of the circles is a measure of how focused a text is on industrialization. In general, there does seem to be a correlation between how focused a text is on the topic of industry, and how progress oriented the language is. Since these trends began in the 1700s (other data in their paper shows very little change in progress or industrialization language in the 1600s), before industrialization began in earnest, Almelhem and coauthors take this to be consistent with Mokyr’s theory: in England, there began to be a belief in the possibility of progress associated with texts on industry.

Back to Today

OK, so changes in text patterns in England, circa 1500-1900 may have anticipated changes in the rate of technological progress. That certainly doesn’t mean changes in language always have that effect - reverse causality seems also to be possible, where faster technological progress leads people to write more favorably about progress. But let’s return to the present and more carefully examine the evidence that there is a genuine change in our language about progress.

Burn-Murdoch uses the google ngram dataset to generate his figure of changing word frequency. This dataset is a collection of about 8 million books that have been scanned by google. Using the dataset to track broad cultural changes is controversial, so in this section I’m going to basically kick the tires of the above chart in several different ways. As a spoiler, I will conclude that the claim that our interest in progress has declined can’t be easily dismissed.

The big problem with using Google Ngram data is that its text does not represent a random sample of text, and any time you are working with non-random samples all sorts of biases associated with how a sample was created can creep into your analysis. Younes et al. (2019) provide some guidelines for using google ngrams for studies. First, they advise checking that trends hold across different languages - a trend that is consistent across multiple languages is less likely to be driven entirely by compositional changes, if the corpuses google assembles for different languages have different biases. Younes et al. (2019) also advise looking at whether synonyms display similar trends. We have a bunch of synonyms for progress, but adding them all together might mask variation in the constituent words.

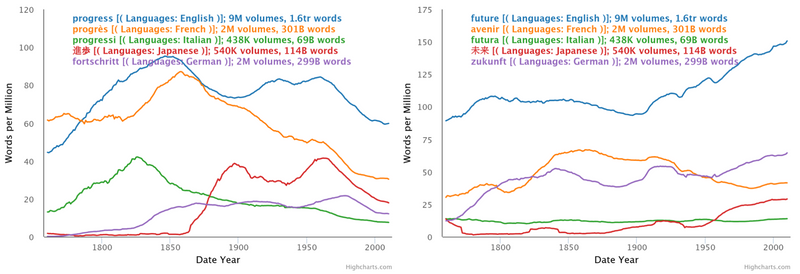

And indeed, we do see some evidence that adding together the frequency of synonyms for progress does obscure some interesting variation. In the figure below, I separately examine trends in English, French, and German.2 For all three of the languages above, the word “future” in English and its equivalents in French and German tends to enjoy a long upward rise, while the other words associated with progress are much more consistently down at the end of the period. In the figure below, I’ve broken out “future” and its French/German equivalents, but left the other progress word synonyms as a bundle to keep the charts tidy. But I did check and “advance”, “rise”, “improvement” and “progress” do display broadly similar trends.

We see a fairly consistent story across these languages. Notably, if we exclude the equivalent words for “future” from our list of progress synonyms, there is a significant decline in progress words across English and French around 1960, and a similar decline in Germany in the 1970s (the blue line). Words for “future”, on the other hand, tend to be up over the whole period in each language.

Compared to “progress”, “rise”, “advance”, and “improvement”, it’s notable that “future” is a more ambiguous marker of sentiment about progress. The word can be used just as easily to convey concern and worry over the future, as it can be used to convey an expectation of improvement.

As another check, we can abandon Google and turn to the same Hathitrust digital library that Almelhem et al. (2023) used in their analysis of words in the run-up to the industrial revolution. The Hathitrust bookworm project makes it possible to study changing word frequencies in the digitized collection of participating academic libraries. To the extent the curation of these library corpuses is distinct from the curation of the google ngram dataset, then if they display similar trends that’s another reason to believe composition effects are not the main driver of changing word frequencies.

Below I look at how frequencies for the words “progress” (left) and “future” (right), and their foreign equivalents, change across the English, French, German, but also Japanese and Italian collections of participating libraries.3

A few broad trends match the google ngram data. Across the five languages, the frequency of the word “progress” and foreign equivalents rises and then falls (left figure), with a particularly marked decline beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Meanwhile, words for “future” (right figure) generally rise, level off, and then rise again, with French and possibly Italian serving as possible exceptions.

Is the accelerated drop in the frequency of the word “progress” across English, French, German, Italian, and Japanese texts, all in roughly the same decade, evidence of a global vibe shift? It seems at least possible - if I was going to think of an event that might lead to a global reassessment of technological progress, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis would probably make the short list.

But more benign explanations are also possible. For example, after WWII, the modern scientific ecosystem was born, and with it a massive rise in the number of new scientific publications. In Almelhem et al. (2023), scientific publications were associated with neutral language, not progress oriented language. Could it be that the decline in the frequency of progress words in text can be attributed to the entry of large-scale, value-neutral scientific publishing into the global text corpus? I investigated this a bit (see the appendix on the website version), and while it’s true that the word “progress” is used less often in scientific text, so is the word “future.” If the rise of academic publishing explains the decline in the use of the word “progress”, it’s surprising that it would not also have a similar effect on usage of the word “future.” Moreover, even looking within scientific texts, use of the word “progress” is falling over the twentieth century.

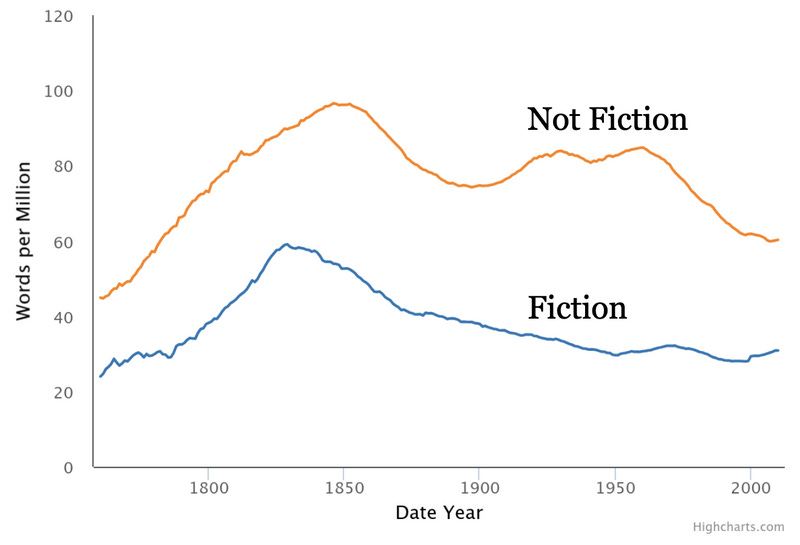

Still, there could be lots of other compositional things going on. For that reason, it’s useful to restrict our attention to a single type of text, to minimize composition change issues. Ideally, this would be a set of text that we have reason to believe broadly reflects broader cultural attitudes. Fiction seems to be a good candidate for that. Below, I plot the frequency of progress synonyms and the word “future” in Google’s corpus of English fiction. English fiction exhibits significantly stronger and longer-run declines in the frequency of progress synonyms then the overall English corpus. Notably, it also shows declines in mentions of the word “future.”

We can also return once more to the Hathitrust digital library. In the figure below, for example, we have the frequency of the word “progress” in their digital fiction collection, and in their digital non-fiction collections. We can see, in proportional terms, that the decline of “progress” in the English language fiction corpus is larger and longer here than for the non-fiction corpus, and that the decline in frequency of the word “progress” accelerated in English generally around 1960 seems to be mostly a story about non-fiction.

Restricting our attention to fiction removes a lot of concerns that changing word frequencies just reflect the composition of a corpus. However, another issue with tracking cultural change via changes in word frequency is that not all words are created equal. The above approaches treat every text the same, whether the books are highly influential or obscure tracts that are never read. It’s not clear a one-word one-vote system is the best way of tracking cultural change.

Varieties of Influence

As an alternative way of assessing changing attitudes towards progress as reflected in fiction, we can look at some work that tries to analyze more carefully selected sets of texts. For example, there are at least two different ways a novel can be considered influential. First, we could equate influence with overall readership. Second, we could equate it with critical acclaim. A number of papers have assembled datasets based on best-selling novels, or novels short-listed for major novel-of-the-year prizes, as a way to identify and study these different kinds of influence. They don’t focus on attitudes around progress, per se, but they do provide interesting insights into how interested novels are in new technologies, and their interest in the present (or future), relative to the past.

To start, let’s look at two studies that document a rift opening up between contemporary best-sellers and critically acclaimed literature. English (2016) looks at when novels are set, while Manshel (2020) looks at how often novels mention new technologies. Both find that critically acclaimed novels are increasingly disinterested in the present.

The following figures, from English (2016) track when novels are set - in the past, present, or future - among US/UK best-sellers and novels short-listed for major awards. Among bestsellers, the share of books set primarily within twenty years of publication (the higher bars on the left) is up slightly from where it was in the 1960s. Meanwhile, the share of best-selling books set in the more distant past (the white bars) has fallen pretty sharply, from a high of 50% in the late 70s to around 10% in the early 2010s. The share of best-selling books set in the future (in dark gray) remains small overall, but has increased by a lot in proportional terms.

But the story is quite different among critically acclaimed novels. There, the share of critically acclaimed books set in the contemporary moment has steadily dropped, from over 70% in the 1960s to below 50% in the 2000s. Meanwhile, the share of critically acclaimed books set in the past has risen steadily, from 20% to over 50% over the same period. Critically acclaimed books about the future remain rare.

Manshell (2020) looks at the share of novels that mention new technologies, comparing it to data on the diffusion of these technologies across the US economy. For radio, television, computers, and the internet, he finds diffusion of these technologies into novels generally follows diffusion through the economy with a lag. But when he breaks his sample into best-sellers and critically acclaimed fiction, he also finds a comparatively recent divergence in novels that mention new technologies. The figure below, for example, compares the share of novels that mention television or computers to the share of households owning a TV or the total number of computers purchased. Prize winners and bestsellers begin to diverge in the 1990s, with best-sellers continuing to track broader adoption of new technologies, and prizewinners falling behind.

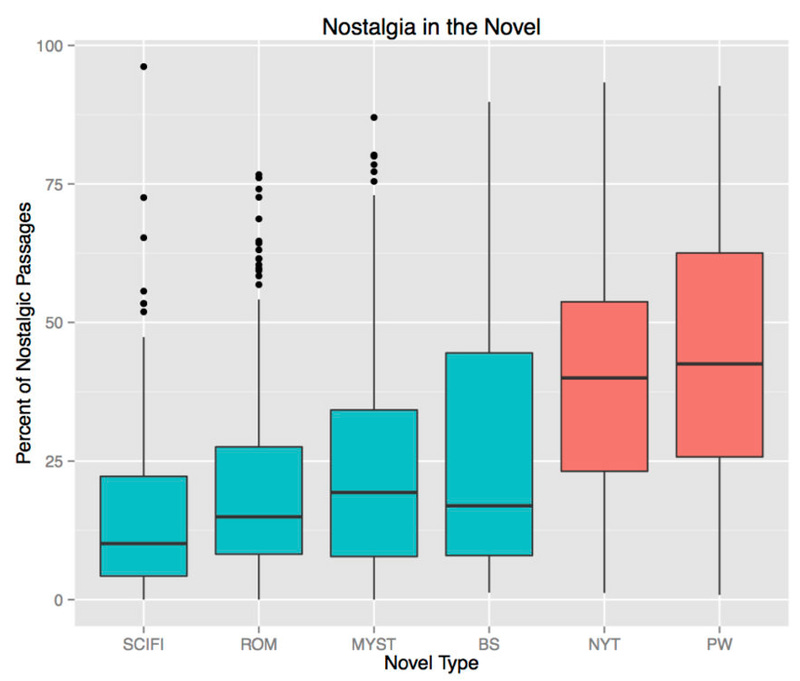

A final paper is Piper and Portelance (2016), which examines variation in the language used in different subsets of books, mostly from the 2000s. In one analysis, they try to identify sets of words that best differentiate books in different categories: what kinds of words are most frequently used in, say, novels shortlisted for major awards but least often used in best-selling novels or science fiction award winners?

One such set of words is the following: afterward, age, born, boy, child, childhood, children, daughter, dream, family, father, girl, life, little, live, memory, mother, old, older, once, recall, remember, school, sometimes, son, winter, young, youth (they actually use the word stems, rather than words, so that boys, families, remembered, etc. would all be counted). Piper and Portelance label this set of words “nostalgic” since they seem to be associated with looking backward. In the figure below, they plot the frequency of these nostalgic words across seven different categories of novel.

Working from left to right, these “nostalgic” words are least common in books in the science-fiction, romance, and mystery genres. Nostalgic words are only slightly more common in best-sellers. But they are increasingly common as we look at nineteenth century realist fiction (C19), books reviewed in the New York Times (NYT), and most common in books short-listed for literary awards.

In another analysis, they manually identify fifty nostalgic passages from each of the above categories (excluding nineteenth century realist fiction). They then use these passages to train an algorithm to classify a 1,000-word passage as nostalgic or not (note, this is a paper from 2016, so they aren’t using contemporary LLMs to do this). They then turn this classifier loose on their text corpus and have it assess what share of 1,000-word passages in a novel are nostalgic. This is a noisier approach, but it also finds nostalgia is much more common among books with critical influence (those reviewed in the New York Times or short-listed for awards) than those with broad readership (genre novels and bestsellers).

Taken together, I think this small literature suggests critically influential fiction is increasingly interested in the past, and as a corollary, probably increasingly less likely to reflect a worldview with progress and optimism about the future of society as important constituents. At the same time, we don’t see much evidence of this kind of shift among more widely read books.

Synthesis

What to make of all this?

I think the academic work discussed here is pretty compelling that critically influential literature is increasingly fixated on the past, at least through roughly 2015. Meanwhile, the word frequency data for fiction seems reasonably clear that words associated with progress and the future have been on the decline for more than a century.

I have more doubts about the broader word-frequency data that documents a sharp decline in progress-related language in the post-war era. The Hathitrust data suggests this recent decline is driven mostly by changes in non-fiction (the google data is a bit more ambiguous). But the non-fiction corpus is a collection of a huge variety of different kinds of texts, so there is a lot of scope for composition changes to drive changes in word frequency. And yet, you see similar trends across many different languages and different collections, and I don’t think it’s easy to explain this away with the rise of academic writing. In the end, I can’t dismiss this line of evidence.

Finally, I have even greater doubts about what this all means for progress. How much do the values and attitudes of critically acclaimed fiction writers matter? How well does word frequency data track broader attitudes towards progress, especially in a world where more of culture is arguably disseminated by other kinds of media? How much do our broad attitudes towards progress matter for overall rates of progress? But I came away from writing this post more concerned than when I started.

The trouble is, standard topic modeling approaches just define topics as probabilities that a paper writing about a topic uses specific words. Sometimes it’s not easy to describe what the topic is about just by looking at the words. So Almelhem and coauthors look at how often a topic appears in the same text with one of nine different topics that do quite clearly belong in the science, religion, or political economy and score topics as being more closely related to science, religion, or political economy if they more commonly appear in texts with the paradigmatic topics for these categories. Once they know how close each topic is to one of these categories, they can infer how close any given text is to them as well, since they know what topics a text contains.

I use google translate throughout to translate English into other languages.

Using the hathitrust digital collection is much more time consuming than google ngram, so I just look for the word progress, rather than all its synonyms.