Innovation disproportionately happens in cities. What is it about packing people together that makes them so innovative?

Last week we looked at a few papers that showed denser neighborhoods with lots of restaurants, cafes, and bars facilitated more innovation, and that the kind of innovation that happens in cities tends to reflect the social milieu of the surroundings. In particular, the residents of dense parts of cities tend to work on a more diverse collection of technologies, and that this is reflected in the kinds of patents they create.

This week I want to look at some evidence that one of the most important functions of cities is to introduce us to new people. I’ll go on to argue being close seems to be very important for initiating and consolidating new relationships, but that once they’re formed it’s no longer so important that you stay physically close - at least from the perspective of facilitating innovation.

Consider a 2018 paper by Christian Catalini. Catalini exploits a natural experiment related to a French university’s 17-year quest to rid its campus of asbestos. Asbestos removal is a disruptive process and whenever a university lab’s turn for renovation came up, it required relocating them to whatever space was available, with little ability for the lab to petition about its location. This meant that labs across campus suddenly found themselves with new neighbors, or separated from old neighbors.

Catalini finds that labs are more likely to collaborate after they are moved into the same building. In the diagram below, year 0 represents the time when two previously separated labs come to reside in the same building.

However, when labs that used to be in the same building are separated, it doesn’t seem to have any impact on their probability of collaborating.

That suggests being neighbors is important for meeting new people, but close proximity isn’t really important after you know about each other. Another line of evidence from Catalini comes from the likelihood two labs would know about each other’s work regardless of their proximity. Catalini uses the publications the labs put out to measure the degree to which different labs work on different topics. It turns out being located in the same building has a big impact on the probability two labs collaborate, when they normally work on different things. For labs that work on similar scientific topics, it doesn’t seem to matter much if they are near or far. In this case, it seems likely the labs don’t need to be close to meet; they were probably always going to meet since they go to the same conferences, seminar series, and so on.

But in Catalini’s study the distances between labs are never that great. The worst case scenario is they get moved across campus; it’s still probably pretty easy to collaborate at those distances. But other work finds similar results for much larger moves.

Agrawal, Cockburn and McHale (2006) look at the citations patents receive when an inventor moves. For example, suppose Ada is an inventor in Ames, Iowa who moves to New York City. Once in New York Ada comes up with a new patented invention. Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale show inventors in Ames are more likely to cite Ada’s new patent then are inventors of technologically similar patents from cities equally far from New York. It’s like the Ames inventors have kept in touch with Ada and know what she’s working on. Indeed, 80% of the increased citations Ada receives from Ames can be attributed to people who either (1) worked on a patent with Ada back when she was in Ames or (2) worked at the same organization as Ada back when she was in Ames. These are precisely the kind of people we would expect to know Ada personally.

Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale also show this effect is stronger for citations across different technologies. For example, suppose Ada works on lithium battery technology. When she moves to New York, she receives about 135% as many citations from other lithium battery inventors who are located in Ames, than she receives from lithium battery inventors who are located from some other equally distant city (for example, Birmingham Alabama). But she receives nearly 175% as many citations from inventors who don’t work on batteries but reside in Ames, than she does from inventors who don’t work on batteries but reside in somewhere like Birmingham. Again; this is consistent with the idea that being located together in the same city was especially important for Ada to meet people who she wouldn’t normally meet - in this case, people who do not work on the same kind of thing as her.

We can go farther. Miguelez and Noumedem Temgoua (2020) look at citations between patents in different countries, when inventors migrate. They find patents from country A are more likely to cite patents from country B when more inventors have migrated from A to B (this is possible thanks to a nice new dataset that actually tracks migrant inventors). As with Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale, this effect is actually stronger for countries that are otherwise technologically less similar. This is again consistent with the notion that proximity - here, merely residing in the same country - is especially helpful for forming social ties with people who work on different technologies than is typical for the country.

Digging into Academia

But we should always be cautious leaning too heavily on patent citation data. They are a pretty imperfect measure. Another major source of “paper trails” for knowledge are academic papers.

Head, Li, and Minondo (2019) look at citations between mathematics papers as evidence of how knowledge moves through a community of researchers. Specifically, they want to know what kinds of things predict whether paper x cites paper y. For our purposes, the variable of interest is their measure of social ties between mathematicians. They measure this in a lot of different ways: advisor-advisee relationships, whether two mathematicians worked in the same place at the same time, or went to the same graduate school around the same time, etc. Note - by definition - most of these relationships are defined in terms of physical proximity at some point in time. Head, Li, and Minondo find a couple of things that are consistent with what we’ve talked about so far.

First, if you do not include any data on social ties, mathematicians are less likely to cite each others’ work if they live far away from each other. But, when you do include social ties, the strength of this relationship gets cut in half. And, looking only at data from the early 2000s onward, the impact of distance disappears completely once you account for social ties. In layman’s terms, what’s going on is something like this: mathematicians are more likely to cite mathematicians they know, and more likely to know mathematicians who live nearby. But, since the year 2000, the only thing that matters (in the data) is the existence of a social tie. If two mathematicians work in the same department and then one moves away this doesn’t really impact the likelihood that they cite each other’s work. It’s the same kind of finding as we had for patents.

Moreover, as with the patents, the importance of social ties is stronger for mathematicians who work in different fields. Again - proximity helps forge relationships, especially relationships that would not normally form in the course of keeping up to date on the field. And those relationships remain pretty durable to moves.

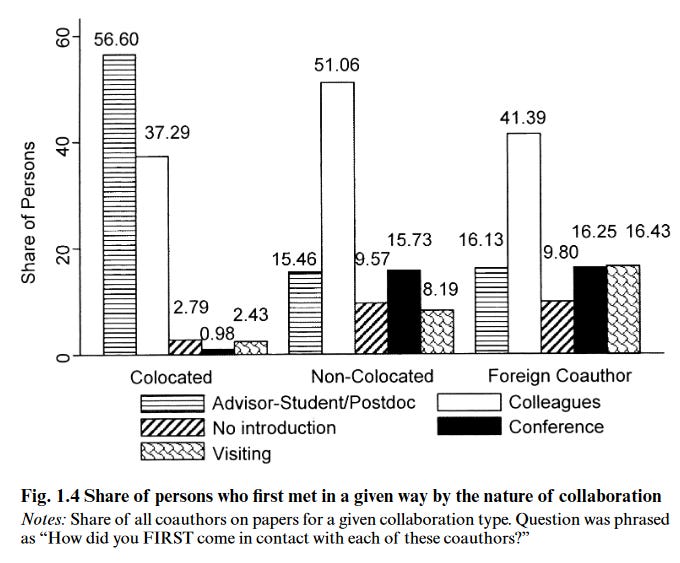

Freeman, Ganguli, and Murciano-Goroff (2015) have some descriptive data on distance and academic collaboration that’s also consistent with this. Looking at 126,000 papers in the fields of particle and field physics, nanoscience and nanotechnology, and biotechnology and applied microbiology, they don’t find any consistent evidence about the impact of having geographically distant coauthors. When all the authors are based in the USA, the citations received by papers authored by geographically distant coauthors are no different than those received by geographically proximate ones in two of the three fields (international collaboration did tend to reduce citations in all cases). But even if it’s possible to productively collaborate at a distance, a strong majority of coauthors first met while they were geographically close (either as colleagues or advisors and advisees).

Tying it together

So, across a lot of contexts we find evidence consistent with this story: innovators meet other innovators who live nearby, whether they work in the same field or not. Once a relationship is formed, it remains pretty productive even after you get subsequently separated, in the sense that you can still collaborate well or at least learn from each other.

Next week’s post will be about what kind of knowledge tends to be useful for an innovator to know: near, far, or something in between?

If you liked this post, you might also like Cities as a platform to mix up knowledge.

Share this post