Innovation disproportionately happens in cities. Carlino, Chatterjee, and Hunt (2007) find, all else equal, that doubling the number of jobs per square mile is associated with 20% more patents per capita. Why? What is it about packing people together that makes them so innovative? I’ll argue in the next few weeks that a big part of the answer is that it’s about meeting new people.

This week, let’s have a look at three suggestive recent papers. Berkes and Gaetani (2020) have data on population density and patenting at the level of the county sub-division (CSD), which is a smaller geographic area than an entire city. How do really dense parts of the country differ from less dense parts? For one, they tend to house inventors working on lots of different kinds of technology.

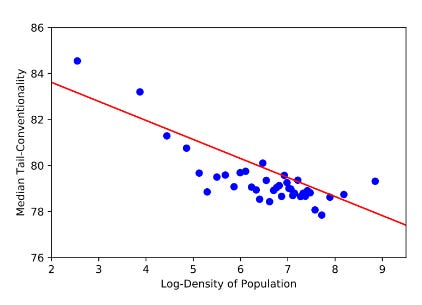

Berkes and Gaetani come up with a measure of the technological diversity of patents in a particular CSD using the technology classifications assigned to patents by the USPTO. When their measure is low, it means that if you pick two patents at random from a given CSD, the technology classes the patents belong to are not usually found together in the same place. As you can see below, the more densely populated a CSD (horizontal axis), the more unusual combinations of technologies you get if you pick two patents at random from that CSD.

So, we can imagine that means there are a lot of people working on different technologies, all milling around in a tightly packed corner of some city. Maybe they bump into each other, talk about their work, and sometimes this sparks a new idea. The inventions and patents that emerge from those spontaneous encounters are more likely to reflect unusual combinations of knowledge. And in fact, patents in more dense parts of the country tend to cite more unusual combinations of technology.

As in the first figure, this is a measure of how unlikely it is that the technology classes of two cited references in a patent are found together. The lower the number, the weirder it is for the same patent to cite these two classes. So, if you live in a place where lots of people are packed into a small area, you likely have a lot of neighbors working on different technologies, and that gets reflected in the kinds of technologies that end up being built there - they draw on diverse sources of knowledge.

Berkes and Gaetani’s paper has a lot more interesting findings, but let’s keep our eyes on evidence about meeting people and move on.

Next, let’s look at a 2020 paper by Maria Roche. Roche is not focused so much on the people who reside in a particular corner of a city, but rather the structure of the city itself. Specifically, she has a measure of the density of walkable streets at different US census blocks. The notion here is that a higher density of streets (importantly, with sidewalks) facilitates more serendipitous meetings. And, indeed, after controlling for many possible confounding variables she finds places with a higher density of streets have more patents, though the effects are tiny (10% denser streets leads to 0.04% more patents). She also finds the denser the streets, the more likely patents are to cite other patents from the same census block. Again, it’s consistent with people meeting each other at a higher rate, exchanging ideas, and then inventing based on what they learn.

Are people really just running into each other on the street, stopping to chat, and then coming up with an invention? Probably not. The streets are a proxy for the existence of other structures that facilitate socializing and mixing with other people. One such place is a restaurant or bar. In fact, Roche finds the impact of density is significantly stronger for places that have 5 or more restaurants, cafes and bars. Increasing the density of walkable streets by 10% in a census block with at least 5 restaurants, cafes or bars is correlated with 0.4% more patents (10x as strong!).

Another paper looks specifically at the impact of bars on innovation.

Why should bars affect innovation? It’s not so much that inventive work happens in bars. But bars are a key social institution in America. When you are just meeting someone for the first time and wish to know them better, it’s easier to ask them to grab a drink at the bar then to come over for dinner. And unlike workplaces and homes, bars are a “third place” where people commonly come into contact with people they wouldn’t normally see. What would happen to all those social interactions if you shut bars down?

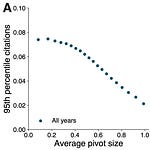

Well, America did just that in the early 20th century, with prohibition. Andrews (2019) looks at the change in patenting in counties affected by prohibition (i.e., counties that had previously been wet ones) as compared to counties unaffected by prohibition (i.e., because they were always dry counties). You can see a big drop in patenting per capita in the wet counties that is not matched in the dry ones right around year 0, which is how Andrews labels the onset of prohibition.

Notice also that patenting rebounds after 3 years. People remain social creatures, and though it took a few years, maybe they eventually built up replacements for the social functions previously served by bars: speakeasies, parties, and church picnics?

When I first read the abstract of this paper, frankly I didn’t believe it. It seemed too cute, and the effect too large. But the paper slowly convinced me it was on to something by drawing together a battery of different lines of evidence. For example:

If this is really about access to bars, then people who don’t frequent bars should be unaffected by the policy change. In the early 20th century, it was uncommon for women to frequent bars and Andrews finds no impact of prohibition on patenting by women. Similarly for ethnic groups that were not as associated with bar culture at the time.

Collaborations between people who are less likely to meet in a bar should be less impacted by the policy. Andrews shows collaborations between inventors who reside in different cities were not impacted by the policy change.

If new social structures had to be built to replace the functions served by bars, it’s unlikely these replacements would perfectly replicate the network of contacts that bars supported. Compared to persistently dry counties, Andrews shows the wet counties showed signs of changes to the social structure undergirding innovation. In formerly wet counties there were fewer patents by people who had worked together prior to prohibition, and the technology class of patents exhibited noticeable shifts, as compared to counties that were unaffected by prohibition.

Taken together, it adds up to a lot of suggestive evidence that interactions with the local social milieu is really important for the amount and type of innovation that happens.

We’ll have another newsletter next week (February 8), which will look at whether the physical proximity of cities is important because it lets you meet new people, or because it makes it easier to work with people you already know.

If you liked this post you might also like this set of three thematically linked posts:

Local knowledge spillovers are weakening, because of cheaper travel and the internet.