Innovators Who Immigrate

Big impacts for people who move to countries where science is happening

Like the rest of New Things Under the Sun, this article will be updated as the state of the academic literature evolves; you can read the latest version here.

You can listen to this post above, or via most podcast apps here.

Talent is spread equally over the planet, but opportunity is not. Today I want to look at some papers that try to quantify the costs to science and innovation from barriers to immigration. Specifically, let’s look at a set of papers on what happens to individuals with the potential to innovate when they immigrate versus when they do not. (See my post Importing Knowledge for some discussion on the impact of immigration on native scientists and inventors)

All of these papers confront the same fundamental challenge: successfully immigrating is (usually) a matter of choice, selection, and luck. For the purposes of investigating the impact of immigration on innovation, that means we can’t simply compare immigrants to non-immigrants. For example, immigrants (usually) choose to migrate, and if they do so because they believe they will be more successful abroad, that signals something about their underlying level of ambition and risk tolerance. That, in turn, might mean they are more likely to be innovative scientists or inventors, even if they had not migrated. Compounding this problem, countries impose all sorts of rules about who is allowed to migrate and many of these rules make it easier to migrate if you can demonstrate some kind of aptitude and talent. That means successful immigrants are often going to be drawn from a pool of people more likely to have the talent to succeed in science and invention, even if they had not immigrated.

These are challenges; but there is also a degree of capricious luck in immigration (and life in general). There are people - perhaps many people - who want to immigrate and have extraordinary talent, but who do not for all sorts of random reasons. Compared to otherwise identical people who do migrate, they might lack information, financial resources, or face higher barriers to legal immigration. Indeed, in many cases, immigration is literally handed out by lottery! The papers we’ll look at employ various strategies to try and find comparable groups of people who immigrate and people who do not, to infer the impact of immigration and place on innovation.

Talented High Schoolers

One way to deal with the selection effect is to try and measure the talent of a sample of both immigrants and non-immigrants and then compare immigrants and non-immigrants who appear to have similar underlying talent. Agarwal and Gaule (2020) and Agarwal et al. (2023) does this with the International Mathematical Olympiads.

The International Mathematical Olympiads is a prominent math competition for high school students from around the world that’s been held annually for decades. Up to six representatives from each country are selected via regional and national competitions, and then travel to a common city and try to solve six different (presumably very hard) math problems. Because it’s an Olympiad, winners take home gold, silver and bronze medals. Agarwal and coauthors know the scores of all the competitors from 1981 to 2000 and then look to see what happens to the competitors later in life. In Agarwal and Gaule (2020) they show that scores on these math competitions strongly predicts later success as a mathematician. That in itself is surprising, given that the talents for doing creative mathematical research may, in principle, differ substantially from performance in a competition.

Their dataset also establishes something else: students from low income countries are less likely to obtain PhDs in math than students with the same score from high-income countries. In Agarwal et al. (2023) they use this dataset to look at the different fates of those who immigrate from their home country and those who do not. On average, a migrant is about twice as likely to be employed in academia as a mathematician as someone from the same county who got the same math score but did not migrate.

Of course, while math scores help address the problem of selection, this doesn’t really get at the problem of choice. Perhaps people who really want to be mathematicians are disproportionately likely to migrate, since the highest ranked mathematics departments tend to be in the USA, and it’s this difference in career intention that explains the difference in career outcomes between migrants and non-migrants.

Agarwal et al. (2023) provides some additional evidence that this is not purely an outcome of career choice. For one, looking only at migrant and non-migrant students who both become math academics (in their own country or abroad), they find the migrants go on to garner about 85% more citations to their publications than their domestic peers (remember, with the same score in math competitions). We might think citations aren’t a great measure of math skill (see my post Do Academic Citations Measures the Value of Ideas?), but they also show migrant academics are about 70% more likely to become speakers at the International Congress of Mathematicians (a non-citation-based measure of community recognition). So among people who ended up becoming academic mathematicians (either at home or abroad), the ones who migrated went on to have more distinguished careers, as compared to their peers who did equally well in high school on math.

But this is still pretty indirect evidence. Fortunately, Agarwal and coauthors also just asked Olympiad medalists directly about their preferences in a survey. From respondents in low- and middle-income countries, 66% said they would have liked to do their undergraduate degree in the USA if they could have studied anywhere. Only 25% actually did. Just 11% said their first choice was to study in their home country. In fact, 51% did.

Why didn’t they study abroad if that’s what they wanted to do? A bunch of the survey evidence suggests the problem was money. For 56% of the low- and middle-income respondents, they said the availability of financial assistance was very or extremely important. Students from low- and middle-income countries were also much more likely to choose a hypothetical funded offer of admission at a lower ranked school than their peers in high-income countries.

Gibson and McKenzie (2014) provides some complementary evidence outside of mathematics. As part of a larger project on migration and brain drain, they identify 851 promising young New Zealanders who graduated high school between 1976 and 2004. These students either represented New Zealand on the International Mathematical Olympiad teams, the International Chemistry Olympiad team, were top in exams, or earned the New Zealand equivalent of the valedictorian rank. Like Agarwal and coauthors, they can then see what happens to New Zealanders who migrate, versus those who remain. They find researchers who moved abroad publish more than those who do not.

As noted, this poses some potential problems; even though we know all these students were talented, those who migrate may have different unobserved levels of skill, ambition, risk tolerance, or something. One way they attempt to deal with this is to focus their attention on the subset of researchers who actually do migrate away from New Zealand, and then looking to see what happens to their research output when they move back. The idea here is those who left were, at least initially, displaying similar levels of skill, ambition, risk tolerance, and so forth (if so, why did they return? We’ll get to that).

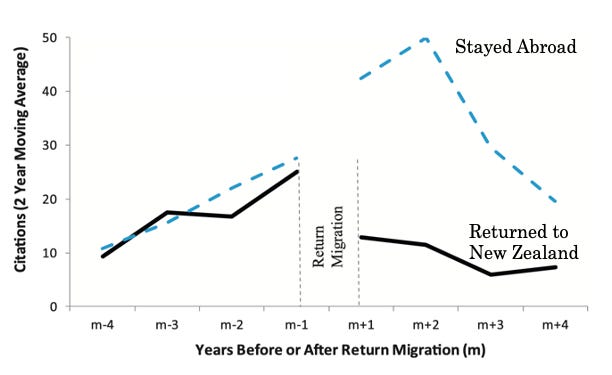

For each New Zealand migrant researcher who returns to New Zealand, Gibson and McKenzie try to find another migrant who stayed abroad, but is similar in age, gender, what they studied in high school, highest degree, and so on. They then look to see what happens to the number of citations to their academic work. While both groups had essentially the same citations prior to return migration, after one group returned to New Zealand, the citations to their work declined substantially relative to the citations of migrants who remained abroad.

Again, we see that being abroad was good for research productivity. But again, perhaps we are concerned that there is an important but unstated difference between New Zealanders who stayed abroad and those who returned home. Perhaps the ones who came back simply couldn’t cut it?

But we actually don’t see much evidence of that. The figure above matches each returnee to someone who stayed abroad based on a number of characteristics. But one characteristic they were not matched on is citations to their academic work. And yet, prior to returning, their citations were on a very similar trajectory. And like Agarwal and coauthors, Gibson and McKenzie also surveyed their subjects to see why they moved back. Most of the answers were not related to individual research productivity, but had to do with, for example, concerns about aging parents, child-raising, and the location of extended family.

Scholarship Restrictions

Another line of evidence comes from Kahn and MacGarvie (2016), which focuses on PhD students who come to America from abroad. The paper’s big idea is to compare students who come on the prestigious Fulbright program to similar peers who were not Fulbright fellows. The students and their matches are really similar in this case: they graduated from the same PhD program, either studying under the exact same advisor and graduating within 3 years of each other, or merely studying in the same program but graduating in the same year. The only difference was the Fulbright students have a requirement to leave the USA for two years after finishing their studies, whereas the matched students faced no such restrictions on their ability to stay.

Kahn and MacGarvie first show that these migration restrictions matter; whereas 66% of foreign students doing PhDs in the USA end up remaining, only 12% of the Fulbright fellows do. They then estimate the impact of being abroad on future academic outcomes, but using a statistical model (instrumental variables) that tries to identify the impact of being abroad deriving solely from the restrictions imposed on the Fulbright program. With this approach, they find leaving the USA due to Fulbright requirements is associated with about 65% fewer publications and fewer citations received, and nearly 80% fewer publications in high-impact journals.

Moving Back to China

Shi, Liu, and Wang (2023) takes a similar approach as the above to evaluate the impact of China’s Young Thousand Talents program. This is an ongoing effort to increase China’s domestic scientific capacity by attracting talented scientists to move to China with salary subsidies and research funding. The program isn’t restricted to Chinese citizens, but in practice that’s mostly the population who chooses to take up the offer.

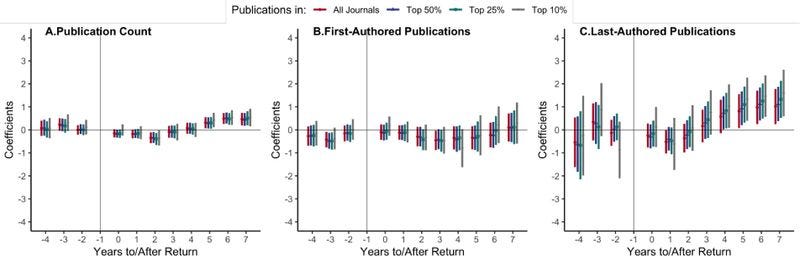

Shi, Liu, and Wang focus on 339 Chinese scientists who obtained PhDs abroad and then moved back to China as part of the program. Similar to Kahn and MacGarvie, they compare this population to a set of Chinese scientists who went to the same overseas university, in the same field, and graduated within three years, but chose to stay abroad. They also try to identify scientists with similar publication and citation trajectories, prior to the date of the return to China.

The figure above plots the publication trajectory of returnees, relative to those who stayed abroad. After a few years of adjustment, those who returned start publishing more than their peers who stayed abroad, with this increase concentrated in last-authored publications (which signals that the scientist is running a lab).

Why are migrants more productive?

In the above, moving abroad is associated with more productivity for mathematicians. Returning home is associated with lower productivity among New Zealand migrant researchers and Fulbright scholars. But returning home is associated with higher productivity among Chinese scientists. What’s going on?

There’s a pretty simple story that runs through all these studies. It’s not migrating that’s good for scientists, it’s about migrating to a place that’s good for science. That might mean a place with the resources to conduct science, or it might mean being in a place with lots of good scientists to collaborate with. Most of the time, it means both, since good scientists tend to go where they have the resources to conduct science. Most people intuitively know this and hence they don’t move (moving is a pain!) unless they think it’ll be good for their career. Hence, the reason we see such a big impact on moving is because people are disproportionately likely to move to places good for science.

For example, in Agarwal et al. (2023), which looked at the effect of moving on the careers of mathematicians, the authors also tried to break down the impact of moving by destination. The USA houses more top math universities (by various ranking) than any other country, and tends to compensate academics well by international standards, so if the moving effect is mostly about moving to places with more support for science, we might expect to see a bigger impact among mathematicians who move to the USA. Indeed, Agarwal and coauthors find that moving specifically to the USA is associated with receiving four times as many citations as not moving, whereas moving to other countries is associated with “only” twice as many. Migrants to the USA also end up six times as likely to become invited speakers at the International Congress of Mathematicians; again compared to twice as likely for migrants to other countries. (Recall, this is when we compare two people from the same country, who received the same score in high school on International Mathematical Competitions!)

Kahn and MacGarvie’s work on Fulbright scholars also tells a similar story. In their case, they focus on the level of GDP per capita in the country that Fulbright fellows return to. They find the penalty associated with return migration becomes increasingly severe as students return to countries with progressively lower GDP per capita. A student returning to a country whose GDP per capita is at the 90th percentile (i.e., only 10% of students in their sample are from richer countries) receive 6% more citations than those who remain in the USA (though the effect is not statistically distinguishable from zero), those whose GDP per capita is at the 50th percentile receive 45% fewer citations than remaining scholars, and those returning to countries at the 25th percentile receive 55% fewer citations than remaining scholars.

GDP per capita in China is not in the top 10%, and so we might expect a penalty for scientists moving back to China. But the Chinese Young Thousands Talent program is explicitly about providing resources to scientists to do science. Indeed, in another analysis, Shi, Liu, and Wang try to take into account the extra funding Chinese returnees in their sample get, by gathering data on grants and the size of the teams they coauthor with. Once you take into account teams and grants, the impact of returning is more muted; much of the advantage of returning is about getting access to funding and a peer network that Chinese PhD students abroad struggled to get.

Shi, Liu, and Wang also find the biggest impact of the program among returnees for whom the funds from the Young Thousands Talent program probably really mattered: those in fields that most require access to funding, such as chemistry and the life sciences, and those who were probably struggling more to get funds abroad, because they had not secured faculty positions, and were not among the top 10% most productive. Indeed, among scientists less likely to need funding - those in mathematics or physics, those with faculty positions prior to their return, and the top 10% most productive prior to return - the impact of returning to China was negative for their productivity, though the effects were too small to be statistically distinguishable from zero.

Even Gibson and McKenzie’s study on migrant researchers who return to New Zealand suggests lower productivity upon return is at least partially driven by funding. In their survey of these scientists, Gibson and McKenzie asked them what policies they would personally recommend to government officials and universities trying to entice researchers to return. The survey responses mentioned things like “low salaries and high teaching loads, poorly funded scientific laboratories and the low success rate of grant funding requests.”

When Inventors Migrate

What about inventors, rather than scientists? Prato (2022) looks at patent-holders in the USA and European Union. Among the 1.2mn who file more than one patent with the European Patent Office between 1978-2016, she identifies about 1500 who do so from the USA in some cases and the EU in others, which forms her set of migrating inventors. For each of these migrating inventors, she finds another inventor from the same country with a similar patenting career up to the year the migrant starts patenting in the other region. This is meant to be her set of comparable inventors, if we think patenting history accurately captures things like talent, ambition, and all the other potential differences between immigrants and non-immigrants that we’re worried may be confounding our results. She then looks to see if the patenting trajectory of these groups diverges in the years after half of them immigrate. As we can see below, it does.

In general, inventors who move take out about 40% more patents per year after they move, as compared to inventors from the same country with a similar patent career up until the year the immigrant moved.

Note, these effects stem entirely from migration between comparatively rich countries (the EU and the USA). About 65% of these migrants moved from the EU to the US and 35% went in the other direction. This is not so much a story about people migrating from a place where probably do not have the resources to invent to a place where they do. Instead, Prato argues this is a story about how migration expands your inventor network and allows you to work in the place best suited for your particular technology field.

How much is at stake?

In one way, the results of these papers are not surprising: moving to places with more resources (and peers?) to do science raises your output of science (and invention). But what is perhaps more surprising is how large the implied size of moving is.

As one point of comparison, several of these papers report an estimate of citations received by academic work.1 Agarwal and coauthors find moving to the USA raises citations to math publications four-fold, or 2.5-fold if you restrict attention to people who become a math academic at home or abroad. Gibson and McKenzie find similar results by comparing New Zealander migrants who return or stay abroad - the ones who stay abroad get up to four times as many citations as those who return. Kahn and MacGarvie find PhD students who stay in the USA get 4-6 times as many citations to their work as their peers in the same program who end up moving back to a country with GDP per capita outside the top 25%.

That’s a pretty consistently large effect. And we get similar kinds of results when we look at other proxies for scientific achievement, whether it’s counting publications, patents, or becoming an invited speaker to the International Congress of Mathematicians. Moreover, Agarwal’s survey results suggests, in math (and it’s hard to believe only in math), there is a large population of talented students who want to study abroad but can’t.

Still, it’s a bit hard to see how this cashes out in terms of it’s ultimate impact: while faster progress in science would probably lead to faster progress in technology, it’s tough to say much about how much faster things could be with this data.

One estimate of the potential impact comes from Prato (2022), which builds a model of the innovation/immigration/trade economy between the US and EU. The model takes into account many subtleties, such as the fact that people with more talent for inventing are more likely to move to places where the rewards for invention are higher, and in turn benefit from working with other high skilled inventors. Her model implies if the USA doubled the H-1B visa cap from 65,000 to 130,000, it would raise the real GDP per capita growth rate in each region by 9% in the long run.

But there’s reason to think that’s an under-estimate of the ultimate impact. Prato’s model is calibrated on migration between the US and EU, two regions with the resources to fund invention and science. As we’ve seen, the impacts of immigration are likely to be much stronger for other regions.

Thanks for reading! As always, if you want to chat about this post or innovation in generally, let’s grab a virtual coffee. Send me an email at matt.clancy@openphilanthropy.org and we’ll put something in the calendar.

These papers have multiple analyses each, and so some of the estimates listed here differ a bit from the estimates noted earlier because sometimes I pulled from different analyses.