January 2022 Updates

Facebook friends, more on patent libraries, and rising penalties for changing research

New Things Under the Sun is a living literature review; as the state of the academic literature evolves, so do we. Here are three recent updates.

Proximity, who you know, and knowledge transfer: Facebook edition

The article Why proximity matters: who you know is about why cities seem to do a disproportionate amount of innovating. The article argues that an important reason is that proximity facilitates meeting new people, especially people who work on topics different from our own. These social ties are a channel through which new ideas and knowledge flows. The article goes on to argue that, once you know someone, it’s no longer very important that you remain geographically close. Distance matters for who you know, but isn’t so important for keeping those channels of information working, once a relationship has been formed.

The article looks at a few lines of evidence on this. Diemer and Regan (2022) is a new article that tackles the same issue with a novel measure of “who you know.” Below is the new material I’ve added to my article, to bring in Diemer and Regan’s new work. The discussion picks up right after describing some evidence from Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale that inventors who worked together in the past continue to cite each other work at an elevated level after they move far away from each other.

While professional connections are probably the most likely to be useful for inventing, they are not the only kind of connection people have. If I make friends with people at a party, these friendships might also be a vehicle for the transmission of useful information. Diemer and Regan (2022) begins to address this gap with a novel measure of friendships: Facebook data. They have an index based on the number of friendships between Facebook users in different US counties, over a one-month snapshot in April 2016. Unfortunately, this measure of informal ties isn’t as granular as what Agrawal, Cockburn and McHale were able to come up with. If you’re an inventor with a patent, this Facebook dataset doesn’t tell the authors who your friends are and where they live; instead, it tells them something like, on average, how strong are friendship linkages between people in your county and other counties. Still, its one of the first large-scale datasets that lets us look at these kinds of social ties.

Diemer and Regan want to see if these informal ties facilitate the transfer of ideas and knowledge by once again looking at patent citations. But this is challenging, because there are a whole host of possible confounding variables. To take one example, suppose:

you’re more likely to be friends with people in your industry

everyone in your industry lives in the same set of counties

you’re also more likely to cite patents that belong to your industry

That would create a correlation between friendly counties and citations, but it would be driven by the fact that these counties share a common industry, not informal knowledge exchange between friends.

Diemer and Regan approach this by leveraging the massive scale of patenting data to really tighten down the comparison groups. Their main idea (which they borrowed from a 2006 paper by Peter Thompson) is to take advantage of the fact that about 40% of patent citations are added by the patent examiner, not the inventor. Instead of using cross-county friendships to predict whether patent x cites patent y, which would suffer from the kinds of problems discussed above, they use cross-county friendships to predict whether a given citation was added by the inventor, instead of the examiner.

The idea is that both the patent examiner and the inventor will want to add relevant patent citations (for example, if both patents belong to the same industry, as discussed above). But a key difference is that only the inventor can add citations that the inventor knows about, and one way the inventor learns about patents is through their informal ties. So if patent x cites patent y, no matter who added the citation, we know x and y are probably technologically related, or there wouldn’t be a citation between them. But that doesn’t mean the inventor learned anything from patent y (or was even aware of it). But if patents from friendly counties are systematically more likely to be added by inventors, instead of otherwise equally relevant citations added by examiners, that’s evidence that friendship is facilitating knowledge transfer.

Diemer and Regan actually look at three predictors of who added the citation: cross-county friendships, geographic distance between counties, and the presence of a professional network tie between the cited and citing patent (for example, is the patent by a former co-inventor or once-removed co-inventor). And at first glance, it does look like geographic distance matters: it turns out that if there is a citation crossing two counties, the citation is more likely to have been added by the inventor if the counties are close to each other.

But when you combine all three measures, it turns out the effect of distance is entirely mediated by the other two factors. In other words, once you take into account who you know, distance doesn’t matter. Distance only appears to matter (in isolation) because we have more nearby professional ties and friendships, and we are more likely to cite patents linked to us by professional ties and friendships. Consistent with Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale’s finding that 80% of excess citations from movers comes from people who are professionally connected, Diemer and Regan find professional network connections are a much stronger predictor of who added the citation than friendliness of counties, though both matter. Lastly, as with Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale, when patent citations flow between more technologically dissimilar patents, the predictive power of how friendly two counties are looms larger. That’s consistent with friendships being especially useful for learning about things outside your normal professional network. But the bottom line is this - distance only matters, in this paper, because it affects who you know.

Even more knowledge transfer: reading edition

Let’s stick with the theme of knowledge transfer for a moment. The article Free Knowledge and Innovation looked at three studies that document improving access to knowledge - via the Carnegie libraries, patent depository libraries, or wikipedia - has a measurable impact on innovation. Of these three studies, one by Furman, Nagler, and Watzinger looked at the impact of getting a local patent depository library, by comparing patent rates in nearby regions to the patent rate in other regions that were qualified to get a library but did not (for plausibly random factors). When I first wrote about it, the study was a working paper. It’s now been published and the new published version includes a new analysis that strengthens the case that increased access to patents leads to more knowledge transfer, and more patents. Below is some discussion of this new analysis.

Furman, Nagler, and Watzinger … also look at the words in patents. After all, a lot of what we learn from patents we learn by reading the words. Furman, Nagler, and Watzinger try to tease out evidence that inventors learn by reading patents by breaking patents down into four categories:

Patents that feature globally new words; words that never appeared before in any other patent

Patents that feature regionally new words; words new to any patents of inventors who reside within 15 miles of the patent library or its control, but not new in the wider world

Patents that feature regionally learned words; words that aren’t necessarily new to the patents of inventors who live within 15 miles of the library, but which were not used on any patents before the library showed up

Patents that feature regionally familiar words; those that were already present in patents of inventors residing within 15 miles of the library, even prior to its opening.

To take an example, the word “internet” first appeared in the title of patent 5309437, which was filed in 1990 by inventors residing in Maine and New Hampshire. So patent 5309437 features a global new word (Furman, Nagler, and Watzinger actually look at more than just the patent title, but this is just to illustrate the idea). I live in Des Moines, Iowa, where a patent depository library opened in the late 1980s. The first patent (title) mentioning the word “internet” with a Des Moines based inventor was filed in 2011. We would say that patent features a regionally new word, since no other Des Moines patents had the word “internet” in their title prior to 2011 but patents outside Des Moines did. If, in 2012, another Des Moines based-inventor later used the word “internet” in their patent we would classify that patent as a regionally learned word, since the word “internet” did not appear before our patent library was founded. Finally, a Des Moines based patent without the word “internet” or any other words that are new to the local patent corpus since we got our library would be classified as a familiar words patent.

We would expect patent libraries to be especially helpful with regionally new and regionally learned words. These are signals that inventors in, say, Des Moines, are reading about patents from outside Des Moines and adopting new ideas they learn from them. And indeed, when you break patents down in this way, you see more patents of precisely the type you would expect, if people are reading patents and using what they learn to invent new things.

On the other hand, we wouldn’t necessarily expect patent libraries to be as much help for globally new words, since those words are not found in any library - they are completely new to the world of patenting. Nor would we expect them to be much help for regionally familiar words, since those pertain to knowledge that was already available before the patent library was founded. And when we look at changes in the trend of these kinds of patents, we see patent libraries had no detectable impact.

Special thanks to Michael Rose for bringing to my attention that this paper had been published and updated!

The increasing difficulty of changing research topics

The article Are ideas getting harder to find because of the burden of knowledge? looks at three main classes of evidence that it takes more knowledge to advance the scientific and technological frontier today than it did in the past. For example, scientists and inventors seem to spend more time in training before they make major contributions. Knowledge work is increasingly done in larger and larger teams. And people are specializing more and more.

Hill et al. (2021) provides some interesting new evidence that specialization is on the rise:

Another way to measure specialization is to see if it has become more difficult to make a major intellectual contribution outside your own field. Hill et al. (2021) attempts to do this across all academic disciplines using data on 45 million papers. Specifically, they want to see if papers that are farther from the author’s prior expertise are more or less likely to be one of the top 5% most cited papers in its field and year.

Because they want a continuous measure of the distance between a new paper and an author’s prior work, they have to come up with a way to measure how “far” a paper is from an author’s prior expertise. They do this using each paper’s cited references. Papers that cite exactly the same distribution of journals as the author has cited in their previous work (over the last three years) are measured as having the minimum research distance of 0. Those that cite entirely new journals that the author has not cited at all in the last three years are measured as having the maximum research distance of 1. In general, the more unusual the cited references are for you, the farther the research is presumed to be from your existing expertise.

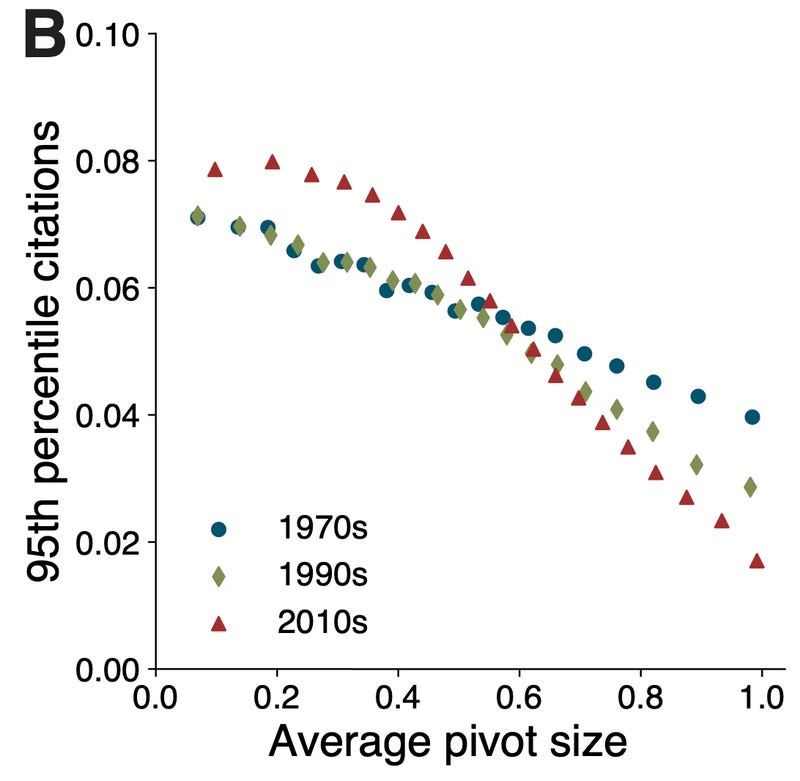

As shown below, the larger the distance of a paper from your existing work (which the paper calls a research pivot), the less likely a paper is to be among the top 5% most cited for that field and year. But each color tracks this relationship for a different decade.

We can see the so-called pivot penalty is worsening over time. If I made a big leap outside my domain of expertise and published a paper that cited none of the same journals as my prior work (a pivot equal to 1 in the figure above), in the 1970s that paper had a 4% chance of becoming a top 5% cited paper in it’s field and year. In the 1990s, it had a 3% chance. And in the 2010s, it had less than a 2% chance.

Two More Things

First, Noah Smith recently wrote the piece below, which cited a number of different articles on New Things Under the Sun:

I agree; more basic research!

Lastly, if you missed it, there was a big announcement about New Things Under the Sun: we’re partnering with the Institute for Progress, where I will be a senior fellow. I wrote a special post about it - read more here.